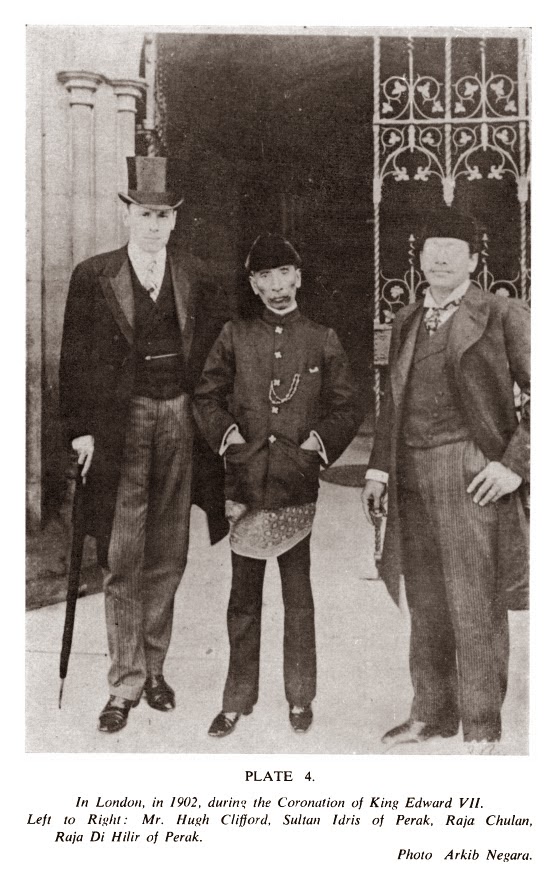

An account by the British Resident at Pahang, Hugh Clifford, of his conversations with Sultan Idris of Perak during the latter's visit to London for the coronation of King Edward VII in 1902, with some startling insights on how the Sultan saw his role in the British Empire.

The then Sultan of Perak had paid a long visit to England some eighteen months earlier and London wrought upon him no new impression. A man of fifty-three years of age, he had passed almost exactly half his life under Malay rule, and half under the new regime inaugurated by Great Britain. A man with eyes wherewith to see and a mind wherewith to judge, compare and think, he was in his day probably the most enlightened rulers of the Native States of the East, and a convinced apostle of British rule.

He had seen in his own time his country pass from a mere wilderness of forest, threaded sparsely by sorry footpaths, into a land surprisingly wealthy and prosperous , over the face of which roads and railways run criss-cross like the meshes of a net. He had seen lawlessness, brigandage, rapine and constant internecine strife vanish and be replaced by a peacefulness unequalled in Piccadilly. He had seen the spear and the kris, which once ruled his world, laid aside in the glass cases of museums, or brought out only on State occasions to deck courtly ceremonials. Moreover, he had seen his own ancestral lands, which of old lay fallow under dense jungle, opened up and made to produce rich revenues; blackest ignorance replaced by education; lack of sanitation by the wise respect for the laws of hygiene; and dire poverty by wealth and comfort.

Though the sentimentalist may mourn the disappearance of much that was picturesque, of much that was attractive, yet these be wonderful changes for any man to have witnessed in the space of half a lifetime, still more to have had a hand in bringing to pass; and without disparaging the wisdom and self-devotion of his European advisers, it must be admitted that Perak owes a large share of its prosperity to the personal efforts of perhaps the greatest of the Sultans who have ever ruled over it.

But the thing that chiefly fired the Sultan's imagination was no one of the revolutions in fact and ideas to which I have alluded, for in all his talks with me it was not upon any of them that he insisted. The cardinal point which he gripped and which obviously filled him with pride, was the contrast between his own position in the world and that of the 27 members of his House who in unbroken line have ruled over his country in the past.

They, he would say, were frogs beneath an inverted coconut shell who dreamed not that there was any world beyond the narrow limits in which they were pent. Shut off from the rest of mankind, living in the hearts of their vast forests, they ruled barbarously over a barbarous people. They were feared by their subjects above the Tiger and, with ample reason, they were loved less than he; they wrought much evil, and no good, to man or beast; and withal they were squalid folk, contented with a paltry state, living ignobly in a world that did not know the insignificant fact of their existence.

"It is wonderful thing," he said to me as we drove off the Horse Guards' Parade after the great Colonial Review. "These be but samples of the King's soldiers in distant lands. I saw our own people - a mere dozen or so - yet I know for how many that dozen stands. Mine is but a tiny country, while others that have sent men here today are vast. What a tremendous host do those whom we have seen this morning represent! Never since Allah first made the world hath there been so mighty a gathering! And this host is the host of my King!"

"It is a splendid thing to think that one belongs to such an Empire - that one is part of it! None of my forebears, stowed away in their forests, enjoyed the greatness that is mine, in that I am myself a portion of something so very great!"

That speech came from his heart, was no mere oriental hyperbole, for he spoke to me as friend to friend, and was not sparing of his criticisms when occasion arose. Observing all things with keen intelligence, criticising all that struck him as unworthy, praising everything that appealed to him as rightly belonging to the great Empire of which he felt himself to be a member, pleased by the kindness and courtesy extended to him, and looking forward with intense interest to the tremendous ceremony which he had come so far to witness, the Sultan of Perak passed the days of his visit until that fateful Tuesday arrived upon which it was announced that King Edward was compelled to submit to an immediate operation for appendicitis and that His Majesty's Coronation was indefinitely postponed. The blow was to us all a heavy one but from the Sultan there came no word concerning his personal disappointment.

"It is the will of Allah," he said simply. "Even our King is His servant to do with what He will; and I, who am the servant of the King, can do little to aid him in his extremity. But that little I will do. Today and tomorrow - until the danger to the King be passed - I go not forth from my dwelling. I will sembahyang hajat - recite prayers for my Intenton of the King's safety. To him my service is due, for to him I owe - everything."

And there I will leave him, clad simply in cotton garments, kneeling and prostrating himself upon his prayer carpet, making earnest supplications to the King of kings for the life of the ruler whose servants, in his name, have brought a malayan people out of the Land of Darkness and out of the House of Bondage. Surely there is hope for a race, let the pessimists say what they will, whose influence wins the love, admiration, confidence and ready support of such men as this - men with the clean mind, the keen intelligence and the kind heart of Sultan Idris of Perak - and makes of them loyal and enthusiastic Imperialists.

Extracted from 'Bushwhacking: and other Asiatic tales and memories' by Sir Hugh Charles Clifford (1929. London: Harper & Brothers)